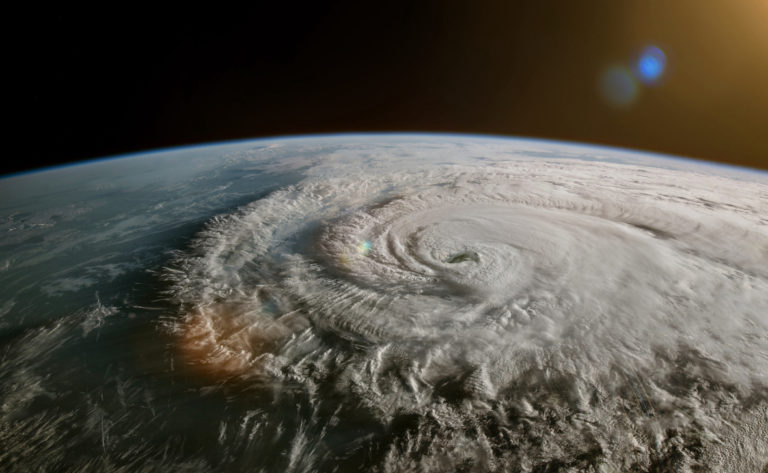

Australia’s east coast cyclones: Using fifty years of data to explore future risks

Researchers from Griffith University’s Coastal and Marine Research Centre used fifty years of data from the Bureau of Meteorology to investigate the characteristics and trends of tropical cyclones.

Dr Clare JM Burns is a lecturer in management teaching and researching values-based leadership, corporate sustainability, and strategy and often exploring organisational culture, ethics, and Indigenous finance. Prior to undertaking PhD studies Clare worked in corporate communications, management, and organisational development for government, multinationals, and not-for profits. For the past 30 years Clare has been a volunteer working with some of the most marginalised people in Australia and overseas, including Africa in a war zone.

Dr Clare JM Burns is a lecturer in management teaching and researching values-based leadership, corporate sustainability, and strategy and often exploring organisational culture, ethics, and Indigenous finance. Prior to undertaking PhD studies Clare worked in corporate communications, management, and organisational development for government, multinationals, and not-for profits. For the past 30 years Clare has been a volunteer working with some of the most marginalised people in Australia and overseas, including Africa in a war zone.