Is it time to re-imagine our fundamental relationship with cities?

We’ve entered 2021 having lived through unimaginable disruption and facing much more, we might well ask ourselves: Will COVID-19 cause a fundamental reimagining of our relationship with cities?

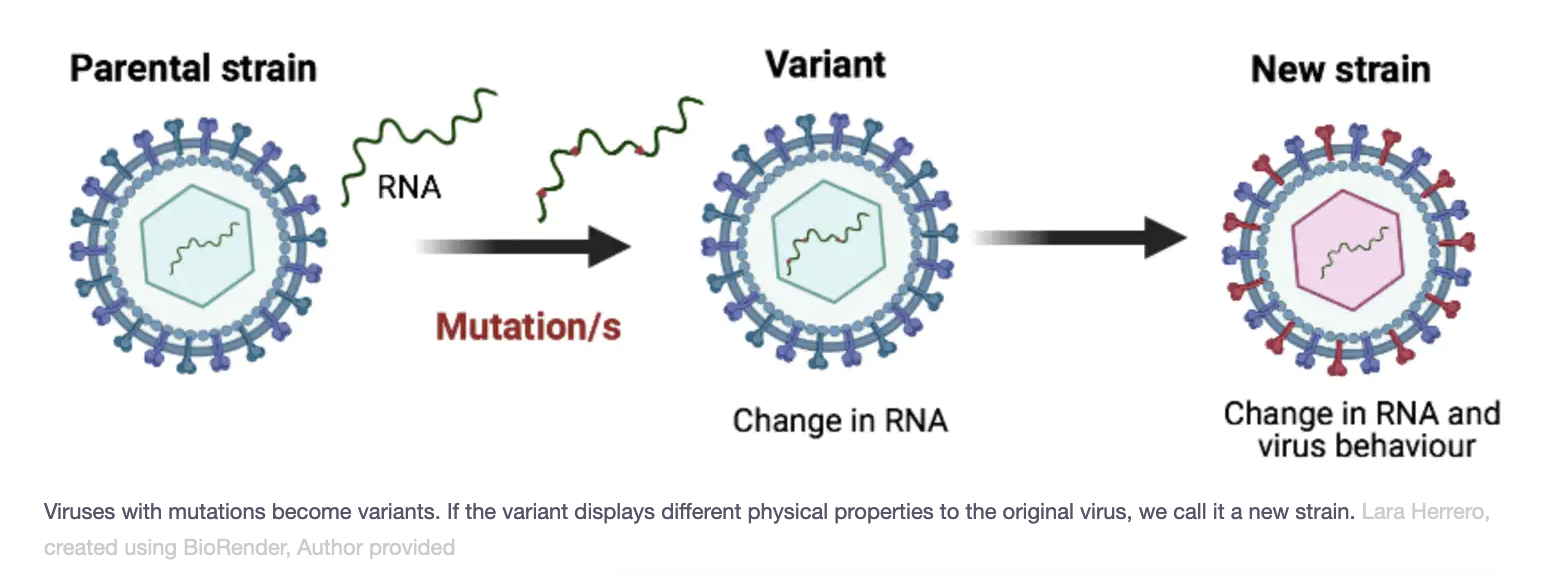

Dr Lara Herrero

Dr Lara Herrero Eugene Madzokere is a final year PhD Candidate in Virology at the

Eugene Madzokere is a final year PhD Candidate in Virology at the