Is The Voice to Parliament necessary?

Eddie Synot from Griffith Law School discusses why The Voice to Parliament is necessary and why this opportunity to change the Constitution should not be missed.

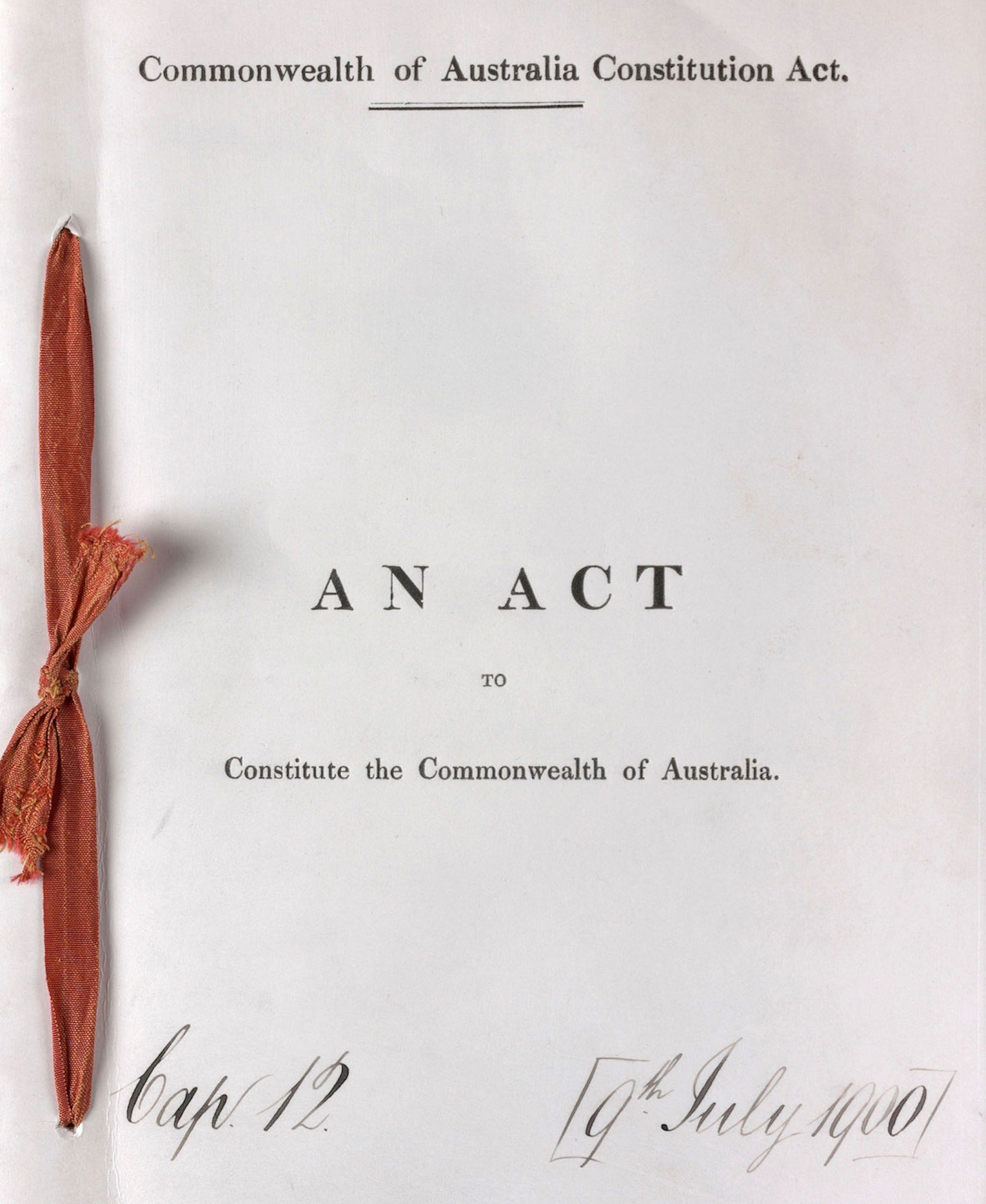

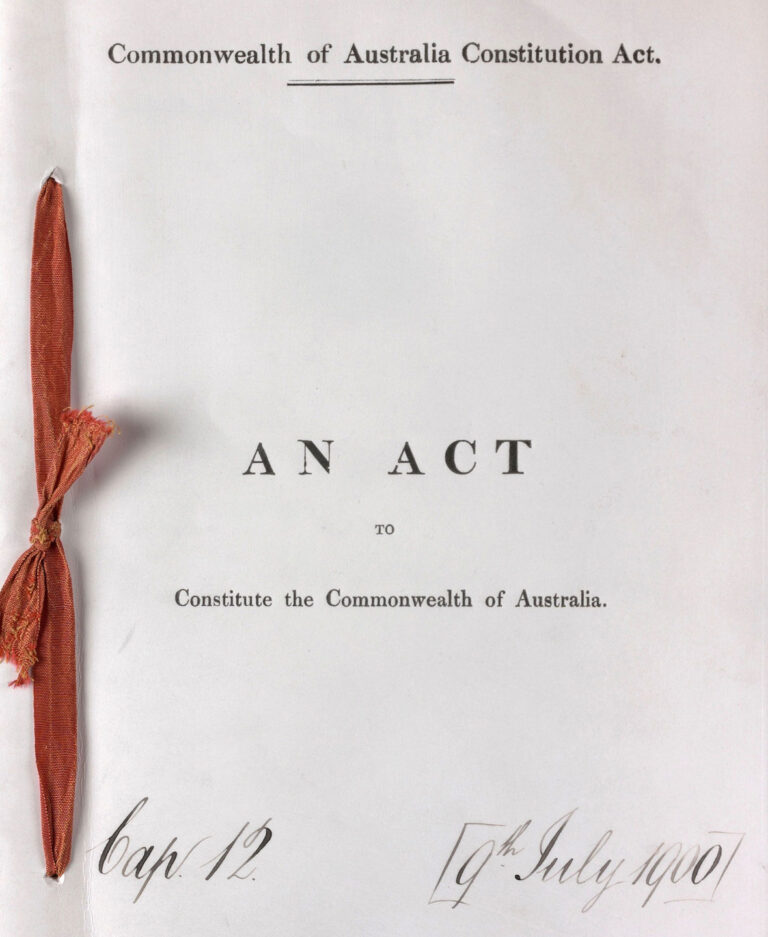

Generally, Australians’ knowledge of their own political institutions is too often found wanting. An Ipsos poll found in 2015, for example, that one third of Australians didn’t know Australia possessed a written constitution. Many more Australians don’t know the purpose of a national constitution, or how that cornerstone document can be changed.

Second, among those who do know, many are suspicious of governments as the drivers of constitutional amendment. This was the case in 1999 when a parliament-appointed head of state was seen as a “politicians’ republic”. That suspicion has only increased in a post-truth social media age where public trust in political institutions has been severely eroded.

Third, constitutional change is logistically difficult in Australia given that a majority of voters in four of Australia’s six states, and a majority of Australian voters overall, must approve a question already passed by both houses of parliament (or by one house after three months’ delay). With just eight amendments approved from 44 attempts in 123 years, its clear constitutional change is exceedingly rare in Australia.

The last successful referendum was 46 years ago when Australians very sensibly agreed that ACT and Northern Territory votes should be included in referendum tallies, that political parties (and not state premiers) have the final say as to who fills a casual Senate vacancy, and that High Court judges should retire at 70. But Australians in 1977 rejected a fourth question: to ensure House of Representatives and Senate elections are held simultaneously.

Worryingly for some, five questions since 1937 have won national majorities but still failed to be accepted by majorities in at least three states. In 1984, an attempt to make Senators’ terms flexible was rejected despite the support of 50.64 per cent of Australians overall.

One conclusion is that Australians are a relatively conservative people who need strong reasons to embrace political change. The fact Australia has seen just eight national governments in more than 70 years offers some evidence of this.

But referendums are more likely to fail when there is a lack of bipartisan political support. For example, Australia’s most enthusiastically endorsed amendment – the 1967 referendum to empower the Commonwealth parliament to legislate for First Nations people, approved by all six states and by over 90 per cent of voters overall – was supported by both the Holt Coalition Government and the Whitlam-led Labor Opposition.

Without bipartisan support – when one side of politics politicises the issue along party lines, often for base electoral opportunism – a referendum is usually doomed to fail, even when the question appears wholly innocuous. The 1988 “Fair Elections” referendum, initiated by the Hawke Labor Government, is a case in point. That referendum would have made it illegal for states such as Queensland and Western Australia to maintain their malapportioned “gerrymanders” that saw (conservative) rural electors’ votes valued more than those of (Labor) urban dwellers.

But, because the federal Coalition under John Howard argued Australia already had “fair” elections, the proposal was framed as a Labor trick – despite the Queensland Liberals urging a “yes” vote – that saw the referendum fail in all states, with a national “yes” vote of just 37.6 per cent.

Given the lack (so far) of bipartisan support for the Voice to Parliament referendum expected to be held later this year – the federal Nationals and the Northern Territory’s Country-Liberal Party have already urged a ‘No’ vote – the fate of the referendum rests with the federal Liberals. While leader Peter Dutton is yet to state his party’s position, Deputy Liberal Leader Sussan Ley’s description of the Voice to Parliament referendum as both a “political trap” and a Labor “vanity project” points to the Liberals also urging a ‘No’ vote.

Critically, opposition to the referendum appears to pivot on five claims.

The first is that a Voice to Parliament is unnecessary given there are already 26 First Nations members elected to Australia’s nine parliaments. Representing 3.1 per cent of all MPs, Indigenous representation approximates the size of the Indigenous population.

Second, it’s been claimed other ethnicities have the right to establish similar bodies constitutionally empowered to advise the national parliament. This argument will find traction among Australia’s large Chinese, Greek and Italian populations.

Third, some worry the Voice to Parliament will become too powerful and, in becoming something of a third legislative chamber, could potentially veto legislation, even that beyond Indigenous affairs. This fear persists despite the reassurances of constitutional experts that such powers are impossible.

Fourth, and arguably the most convincing, is the view that Australian voters, while broadly supportive of any policy enhancing First Nation lives, simply have too little information on which to decide their vote. Once again, history shows that several referendum questions lacked detail of their later effects before the vote but were nonetheless passed. Indeed, Australians in 1967 did not know what path Commonwealth legislative power over Indigenous people would take, but 90.77 per cent of us nonetheless supported the amendment.

Even so, reluctance to support a proposal because of a lack of detail cannot be dismissed as illogical, and it’s up to sectional interests on both sides to supply accurate information and to engage in public debate.

Last, opposition comes from those who worry that, should the Voice become unworkable or obsolete, then removal from the constitution – attained only by another referendum – becomes virtually impossible.

It becomes clear that these fears – shared across sex, class, age and geography – are more than isolated anxieties: they underscore Australians’ small ‘c’ conservatism and their reluctance to embrace change.

If the referendum does fail, it will be decades before the question is revisited constitutionally.

Dr Paul Williams is an Associate Professor of politics and journalism at Griffith University’s School of Humanities, with a special research interest in Australian federal and state elections and voter behaviour. He is also a weekly columnist with The Courier Mail newspaper, and is published in various scholarly journals.

Dr Paul Williams is an Associate Professor of politics and journalism at Griffith University’s School of Humanities, with a special research interest in Australian federal and state elections and voter behaviour. He is also a weekly columnist with The Courier Mail newspaper, and is published in various scholarly journals.

Eddie Synot from Griffith Law School discusses why The Voice to Parliament is necessary and why this opportunity to change the Constitution should not be missed.

Professor AJ Brown discusses Australian constitutional law in relation to The Voice to Parliament as well as the process and outcomes of prior referendums on the nation’s culture and democracy.

Professor Ciaran O’Fairchellaigh writes on the impact of criticisms of The Voice to Parliament will have on the development of Critical Minerals, the reserves of which are located on Indigenous lands. Critical Minerals are essential for renewable energy technologies, the demand for which is projected to rise significantly.