Six ways to improve your teenager’s financial literacy

People need a basic understanding of financial concepts to make good financial decisions. Our newly released research found most students generally do not know a lot about personal finance.

This International Women’s Day we recognise the contribution of women and girls around the world, who are leading the charge on climate change adaptation, mitigation, and response, to build a more sustainable future for all.

This is the critical decade for climate action and all foreign policy interventions will be judged against this global challenge. To meet this challenge, it is time for Australia to adopt the focus and techniques of feminist foreign policy. It is well established that Australia’s reticence to act on climate change is undermining our diplomatic relationships, particular with our near neighbours in the Pacific. As a collective action problem, climate change requires nations to look beyond their own narrowly defined interests and seek collective global solutions.

Feminist foreign policy provides a lens through which we can see climate action as a shared priority, a human security and human rights issue, and one which is central to Australia’s relationships with the region. Additionally, as a framework which emphasises the need for policy coherence between domestic and international issues, feminist foreign policy highlights the need for Australia to take domestic action on climate change in order to fulfil our international role.

Critically, the impacts of climate change are gendered, and so the solutions must be informed by rigorous gender analysis. Feminist foreign policy, with its focus on understanding and transforming the systemic drivers of inequality and marginalization, can further our understanding of the historical contributions of nations to climate change and rebalance of the scales towards the most marginalized who face the greatest impacts

The latest IPPC Sixth Assessment Report on Impacts, Vulnerability and Adaptation (2022) has recognized this need for feminist climate diplomacy, stating that not only are the impacts of climate change heavily gendered, intersectional solutions that promote just and equitable mitigation and adaptation actions to support sustainable development can lessen climate risk:

Structural vulnerabilities to climate change can be reduced through carefully designed and implemented legal, policy, and process interventions from the local to global that address inequities based on gender, ethnicity, disability, age, location and income (very high confidence).

This includes rights-based approaches that focus on capacity-building, meaningful participation of the most vulnerable groups, and their access to key resources, including financing, to reduce risk and adapt (high confidence).

Evidence shows that climate resilient development processes link scientific, Indigenous, local, practitioner and other forms of knowledge, and are more effective and sustainable because they are locally appropriate and lead to more legitimate, relevant and effective actions (high confidence).

To date, Australian diplomacy has not fulfilled this brief. Instead, Australian foreign policy as expressed through the 2017 White Paper has relegated climate issues as just another risk to the region, low on the list. Our national plan takes a technology-driven, neoliberal market solutions approach in which gender is not mentioned once, not to mention other kinds of knowledge and approaches to climate change such as First Nations perspectives.

This IWD we provide practical recommendations for short- and long-term goals for Australia’s climate action – including immediate priorities for COP27.

Australia’s short-term goal must be to take to a much more ambitious national climate action plan (NDC) and Long-Term Strategies to COP27 in November. The long-term goal must be to reorganise DFAT to enable it to tackle the centrality of climate change as a human security risk, acknowledging that current diplomatic methods might also need to adjust. Australia should prioritise working with our Pacific neighbours on climate diplomacy (see further IWDA recommendations here).

To this end:

COP27 gender recommendations (in line with the Women’s Environmental and Development Organisation (WEDO) recommendations for #FeministClimateJustice at the UN Commission on the Status of Women 66 in New York).

Australia has a real opportunity to lead the world in feminist climate justice. There has never been a more critical moment to start.

Professor Susan Harris Rimmer, Climate Justice Lead, Griffith Climate Action Beacon. Susan is part of the Australian Feminist Foreign Policy Coalition and is collaborating with Esther Onyago, Rowena Maguire and Bridget Lewis from QUT and Maria Tanyag from ANU on feminist climate research and this piece represents a collective position.

Professor Susan Harris Rimmer is the Director of the Griffith University Policy Innovation Hub. She was previously the Deputy Head of School (Research) in the Griffith Law School and prior to joining Griffith was the Director of Studies at the ANU Asia-Pacific College of Diplomacy.

With Professor Sara Davies, Susan is co-convenor of the Griffith Gender Equality Research Network. Sue also leads the Climate Justice theme of the new Griffith Climate Action Beacon.

Susan is the 2021 winner of the Fulbright Scholarship in Australian-United States Alliance Studies and will be hosted by Georgetown University in Washington DC.

Follow Sue on Twitter

People need a basic understanding of financial concepts to make good financial decisions. Our newly released research found most students generally do not know a lot about personal finance.

We are entering a uniquely dangerous time in Australian politics Not just from the economic threats following Australia’s performance at COP26 in Glasgow. Compounding these existential threats is the risk that core tenets of Australian democracy, which have become weakened and frayed in the past two decades, will be completely eroded.

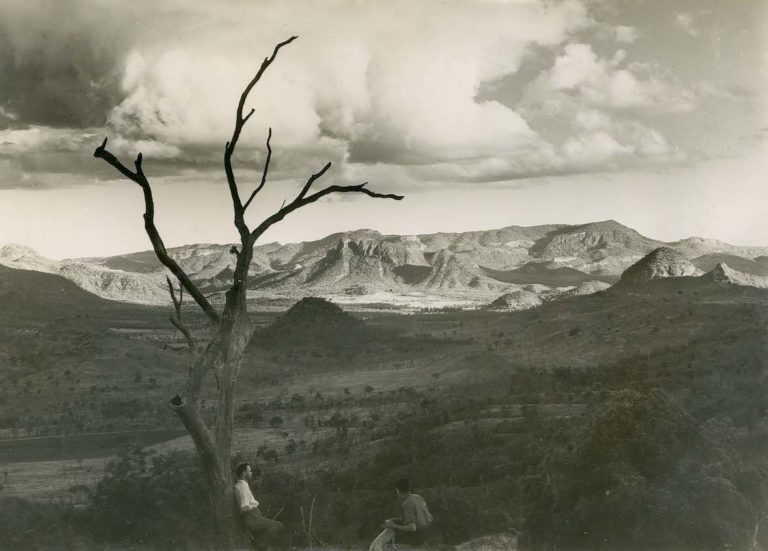

Susan Harris Rimmer on her home town Coonabarabran, she asks “will we look back on those families who gave up on Coona as part of the first waves of forced relocation that will happen due to climate change in Australia? Do people realise climate mobility issues are already happening?