Advice to the 46th Parliament: Integrity and Accountability

Professor AJ Brown on his Top 5 Integrity and Accountability issues that the 46th Parliament need to address.

Water is critical to life and jobs, and large infrastructure projects tend to sway voters at the polling booth. Paired together, it’s easy to understand why the New Bradfield Scheme (the Scheme) was a central policy in the 2020 Queensland election.

This article aims to provide a nuanced conversation over the Scheme. The major issues fall into two broad categories: policy considerations and regulatory controls to protect the environment. The article then considers the success or otherwise, of drought proofing projects in Australia.

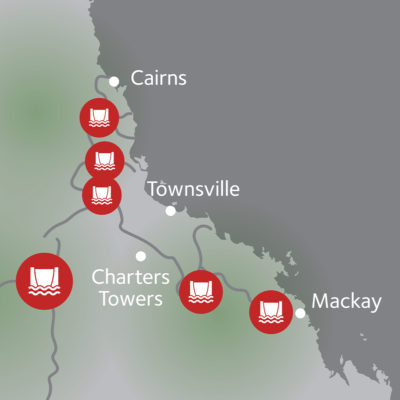

A vast engineering project, estimated to cost about $15 billion, it aims to ‘drought proof’ parts of inland Queensland. Infrastructure is needed to draw water from four rivers along the coast (South Johnstone, Tully, Herbert and Burdekin) into a new large dam at Hells Gate. Then through series of other dams east of the Dividing Range, to feed that water into the Flinders River and tributaries of Kathi Thanda-Lake Eyre which lie west of the Range.

The Hells Gate Dam itself would have a storage of 2,100 gigalitres (GL) and the Scheme will require bringing that water through hundreds of kilometres of pipes, tunnels and channels to create a new “food bowl”.

The Scheme was first proposed in 1938 by John Bradfield, of Sydney Harbour Bridge fame. His idea, as opposed to tunnels in the current version, was to pump and pipe the water over the Range. Queensland government of the time rejected this because of costs and lack of evidence that it would provide benefits.

“However, the grand vision of Bradfield continues to inspire political leaders of all stripes, including Peter Beattie in 2007; Bob Katter in 2008; Barnaby Joyce, Pauline Hanson, and Deb Frecklington in 2019.”

There is yet to be a feasibility study of the whole Scheme but reports of some of its components exist.

The 2018 study of the Hell Gates dam itself states “cost estimate performed cannot be highly accurate given the level of risk attached to the various system [sub] components …”. The LNP propose to finance the building the Scheme from royalties from Galilee Basin, a 247,000 square kilometre thermal coal basin in central Queensland. Royalties from all coal produced throughout state in 2017–2018 amounts to around $3.8 billion, out of which $1.8 billion was from the Isaac region in the Galilee Basin.

Stakeholders point to expected annual royalties, of approximately $220 million each year if one quarter of the coal capacity in the Galilee Basin is mined. Even if all of the royalties across Queensland from coal were to be allocated to build the Scheme, it would take over 5 years to cover capital costs. Recovery of operating costs from customers is another issue.

The National Water Initiative (2004) requires recovery of the “operational, maintenance and administrative costs, and make provisions for future assets refurbishment or replacement from those who use water”. A consultant’s report for another important component of the Scheme (transfer from Hells Gate Dam to Webb Lake for storage) warns that “new projects that require an ongoing subsidy to operating costs (e.g. pumping costs) could be considered extremely challenging.” With the LNP’s promise to cut farmer’s water prices by 20 per cent, it is highly unlikely that these operating costs could be recovered from customers and comply with national water policy.

The Scheme involves traversing land held under native title. Australian water policy recognises pre-existing Aboriginal and Indigenous rights to water, although the extent of that recognition is debatable. So far there is no evidence of consulting with native title owners over the Scheme, although the consultant for a feasibility study for Hells Gate Dam state that two aboriginal groups are in favour of the project. Aboriginal groups in the Wet Tropics, and inland Queensland have been active in preserving cultural heritage and have formed Aboriginal knowledge partnerships for water planning and assessment. There is no suggestion by proponents that Aboriginal knowledge will have a role to inform design or implementation of the Scheme.

Proponents of the Scheme claim that it has environmental benefits — allegedly reducing environmentally damaging water discharge into the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park. While run off from coastal Reef rivers detrimentally affects water quality, there are many other factors affecting Reef health. No other potential environmental threats are mentioned, despite a federal regulatory framework which will certainly apply.

At the federal level, the main regulatory control is the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999. Actions which pose a threat to biodiversity conservation and “matters of national environmental significance” are subject to processes under the Act. It is no surprise that dam proposals fall into this category of “controlled action.” Let’s look at some Queensland examples.

In 2006 the Traveston Crossing Dam proposal involved the construction and operation of a new dam on the Mary River, upstream of Gympie, Queensland. Envisaged as part of the South East Queensland Water Grid, it would improve water security for the growing demand of the region. Comparing storage capacity, the Hells Gate Dam is about 14 times the size of the Traveston Crossing Dam which proposed storage of around 153,000 megalitres (ML).

A better comparison would be of inundation area, but there is no estimate of the former’s inundation area.

A final Environmental Impact Assessment and an independent review by three experts found that that the reach of the Mary River to be inundated by the Traveston Crossing Dam contained “important habitat for the Mary River Turtle, Mary River Cod, Australian Lungfish and the Southern Barred Frog that is critical to their ongoing survival”. These experts also advised that it would be “highly unlikely that the dam would provide suitable foraging and breeding habitat to support the self-sustaining populations of these species”. Further, the experts doubted the effectiveness of proposed mitigation and offset measures.

Another example of the assessment process under EPBC Act is the Nathan Dam’s case in 2008. The Nathan Dam proposal was for an 880 000 ML dam near Taroom on the Dawson River in Central Queensland. Strongly backed by the State government, there were potential benefits for development and economic growth in the State. Environmental groups appealed the Federal Minister’s approval under the EPBC. The Full Federal Court found that the Minister had failed to consider the full range of potential impacts on matters of national environmental significance such as the use of water downstream of the dam for agricultural purposes. This was an error of law, and the approval was not valid.

These two examples point to the need for the Scheme to comply with EPBC Act assessment and approval. It is very likely that a project of this size will have high environmental impact. Besides landscapes affected by construction of infrastructure, use of water in expanding agriculture upstream of Kathi Thanda — Lake Eyre, will detrimentally affect that pristine, fragile landscape.

The management, use and allocation of water whether surface or groundwater is governed by the Water Act (2000). Statutory water plans are in place for each basin in Queensland. The Scheme will involve revisiting at least four Water Plans i.e. Wet Tropics, Burdekin, Gulf and Cooper Creek. Each water plan is based on best available information including environmental assessments; ecological modelling using data collected on the flow requirements of each ecosystem; and social, economic and cultural assessments.

Each of the water plans provide for water for future expansion of use through what is called ‘strategic reserves’. While the Burdekin water plan has a large strategic reserve of 335,000ML which can be allocated towards the Scheme, the rivers in the Wet Tropics are shorter and have far less volumetric flow. For example, Johnson River has a strategic reserve of 3,100 ML and the Herbert River has 8,850 ML as a strategic reserve. Strategic reserves are based on the assessments indicated above, and specify how much water can safely be drawn for use without affecting the riverine ecology. It would be difficult to justify how these strategic reserves would be drastically changed without affecting the environment.

The New Bradfield Scheme is a nation building proposal reminiscent of post war civil engineering feats of the Snowy scheme and the Ord River Irrigation scheme. Mega projects such as the Scheme appeal to voters in times of drought. That is has a vision of epic proportions is an understatement. The Scheme is based on the belief that it is possible to drought proof Australia. In a sense, all dams are based on that belief, but since the World Commission on Dam’s critique in 2000 of the social and environmental impact of large dams, the developed world has largely heeded calls for comprehensive options assessment, consideration of alternatives and demand side management.

Dams in the Murray Darling and the Ord schemes are the two examples of drought proofing projects. The former is an example of how mitigating the environmental impact of large engineering schemes is an expensive exercise not without social costs. Agricultural production in the Ord River Irrigation Scheme ( Stages 1–3) shared by Western Australia and Northern Territory has not fully taken off. Over $1.5 billion has been spent since 1959 and there is criticism that benefits which were promised have not occurred.

Closer to the home of the Scheme is the Burdekin Falls Dam, on the lower reaches of the Burdekin River, completed in 1987 at the cost of $125 million. With a capacity of 1,860 GL it is currently the largest water storage resource in Queensland. In 2015/16 agricultural production from the Burdekin Shire was $566 million representing 4.6% of Queensland’s total production. Commentators based in that region are of the opinion that while this dam provides water security for nearby Townsville it has not delivered on the promise of triggering huge agricultural production.

In response to the Liberal National Party’s plan, the Queensland state government has set up a three person expert panel to conduct a comprehensive examination of the financial, economic, environmental, social and technical viability of the Scheme. Chaired by Prof Ross Garnaut, the panel’s report is expected in August 2021. We shall then see whether the panel’s report supports the preliminary opinion offered here – that the Scheme has far more costs than benefits for Queenslanders.

Professor Emeritus Poh-Ling Tan has experience in legal practice and academia with expertise spanning property law, Asian legal systems to water resource law and governance.

Professor Emeritus Poh-Ling Tan has experience in legal practice and academia with expertise spanning property law, Asian legal systems to water resource law and governance.

She has researched and provided policy advice on aspects of water reform and planning. For many years she served on reference and advisory panels with the Murray Darling Basin Authority, Queensland’s Department of Natural Resources, Mines and Energy, and the OECD’s Water Governance Initiative. Currently she sits on the Advisory Committee for the Australian Water Partnership, Queensland’s Water Referral Panel and the Gladstone Area Water Board.

Professor AJ Brown on his Top 5 Integrity and Accountability issues that the 46th Parliament need to address.

Australia’s COVID-19 vaccination rollout has hit yet another crossroads. Public confidence has wavered following the federal government’s announcement last week that the Pfizer vaccine was the preferred choice for people under age 60.

Looking back over my family tree, the last century has been kind to my ancestors. Many of them have made it to a ripe old age, with some outliving previous generations twice over. But as a member of the next generation to move into middle age (and, if I’m lucky, beyond that), I find myself already ‘burning and raving’ and raging against what I see as narrow options ahead.