2022 Federal Election: Seats to Watch

Griffith University’s panel of politics experts have identified the seats to watch at the 2022 federal election.

In September-October 2021, Griffith University’s Climate Action Beacon conducted the first of five annual Climate Action Surveys. In part longitudinal, these surveys discover *Australians’ thoughts and feelings about climate change and related environmental and climatic events, conditions, and issues. Significantly, this survey maps existing actions being undertaken by Australians alongside their ideas on further personal and societal based climate action. This article summarises how Australians think about, respond to, and significantly participate in climate action.

The story of climate action in Australia is much more complex than the usual broad-brush strokes of trust or not in climate science would suggest. We know from our survey results that most Australians agree that climate change is an urgent issue there is much more to their action, or inaction, on climate and associated environmental issues. Climate action is a part of the historical, political, cultural, social, economic and ecological milieu that defines Australia, its communities and its people. This complexity cannot be smoothed away and so our extensive Climate Action Survey was developed in consultation with diverse disciplines and stakeholders. We also examined existing and established climate change surveys in Australia and elsewhere, to avoid unnecessary replication and to distinguish our own – geared to climate action.

These survey results reflect climate action opinions and attitudes in late 2021. Note this was prior to the 2022 Federal Election campaign, 2022 flood disaster, mass coral bleaching events and before the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released its Sixth Assessment reports.

Across the wide range of climate change variables collected, a distinct profile emerged of who is Australia’s most climate change-concerned and climate change-active.

Generally, Australians displaying high levels of concern and activity typically fell into one or more of the following groups: aged 35 years or under; university-educated respondents; those currently studying; inner-urban residents; people residing in homes in which English is not the primary language spoken; respondents intending to vote for the Greens or Labor Party; and who have had prior experiences of extreme weather, natural disasters, or perceived manifestations of climate change. We do observe concern for climate change in nearly all other respondent segments, but at lower levels.

Women reported being more concerned and more active than men. Older people, rural residents, and school only-educated respondents tended to be the most climate change sceptical, unconcerned, and inactive.

Income was one of the few demographic variables that did not strongly differentiate between those with high and low levels of engagement in the issue of climate change. This selection of comparisons suggests that the findings from the current survey are broadly in line with those obtained in other recent Australian surveys.

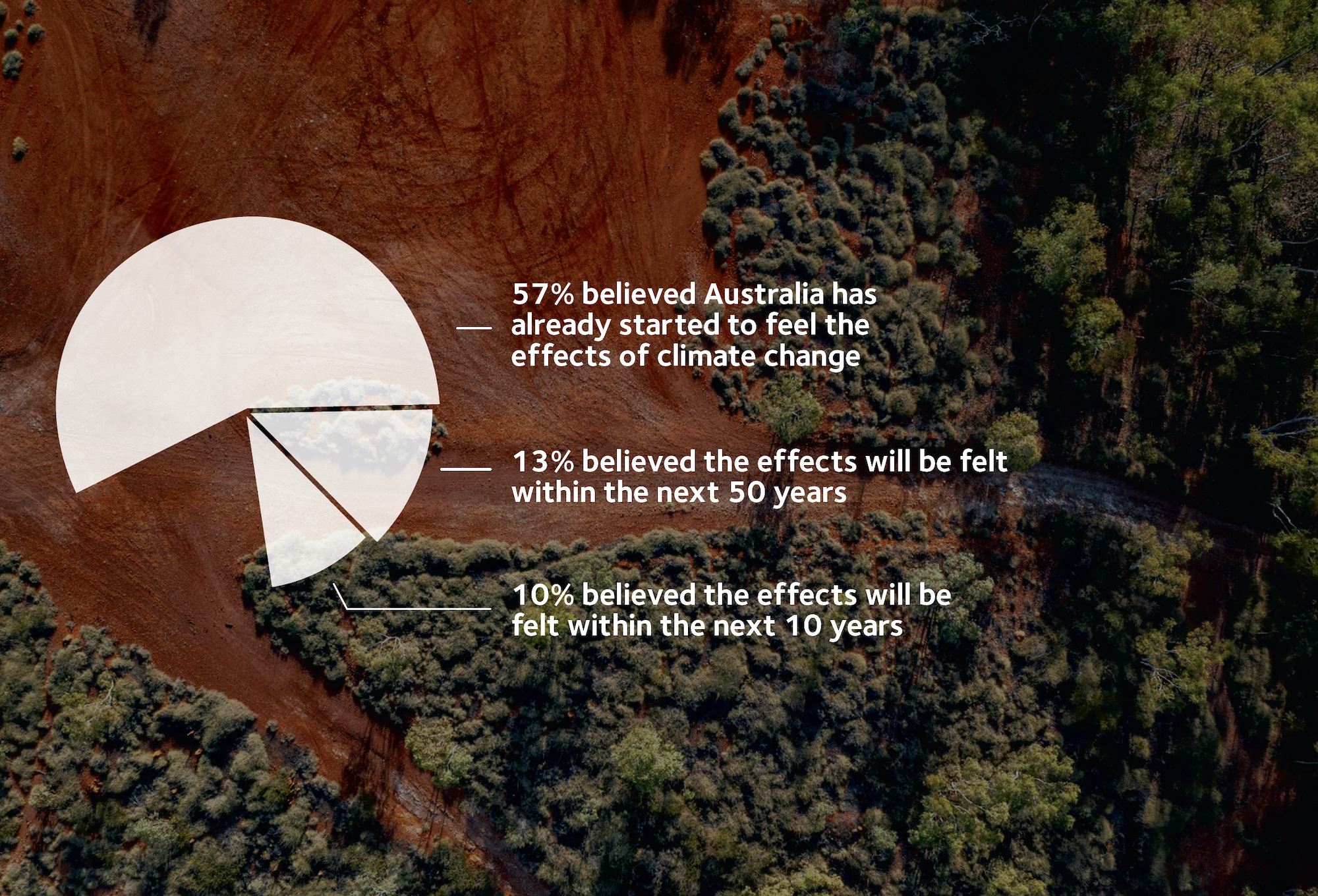

57% of respondents believed that Australia has already started to feel the effects of climate change, 10% believed that the effects would be felt within the next ten years, and a further 13% believed that the effects would be felt within the next 50 years. Only 5% of respondents believed that Australia would never feel the effects of climate change

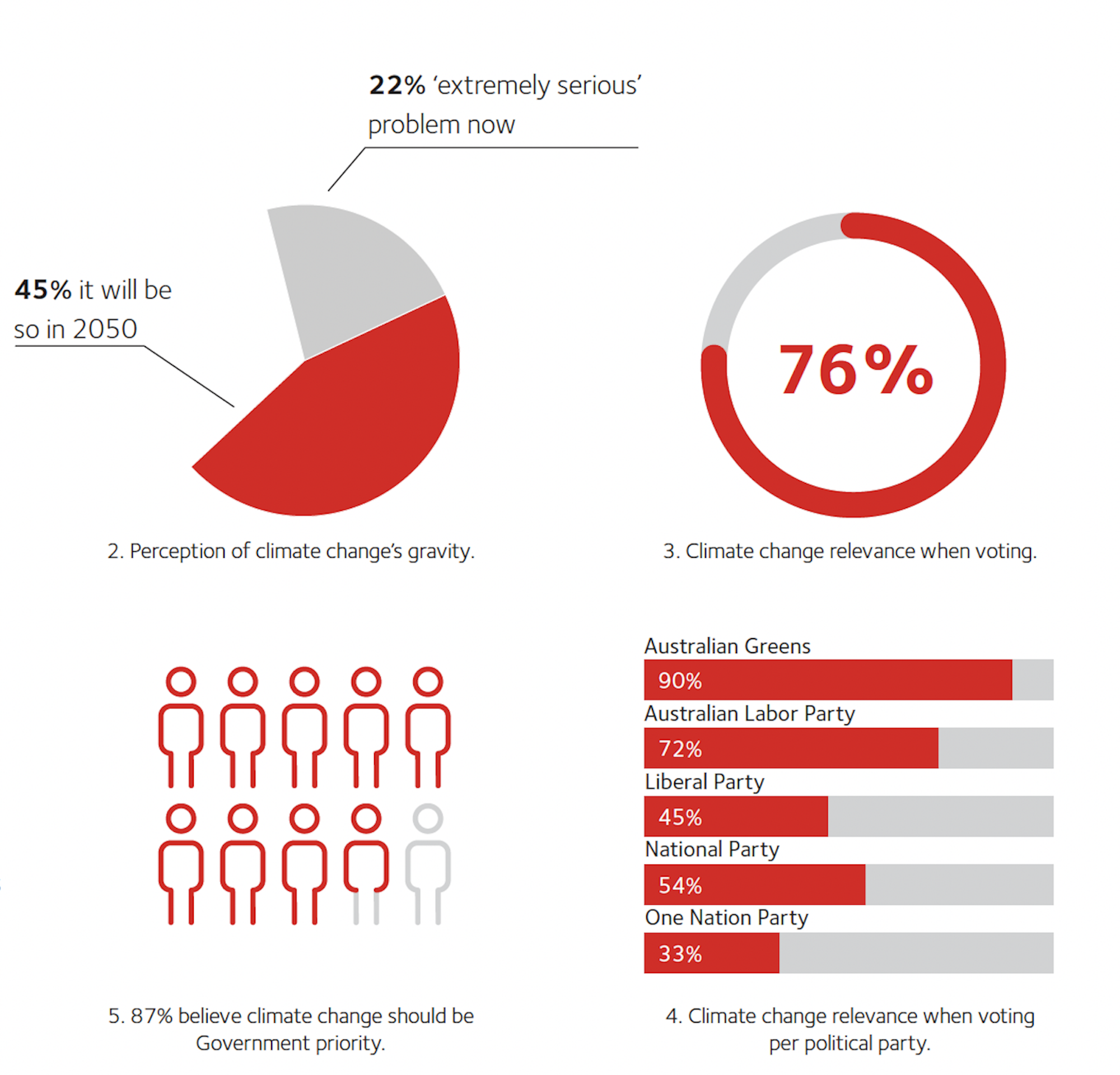

While some of the results surrounding climate change and the federal election were expected – like greater support for climate action amongst ALP and Green voters, there were some surprises. Liberal and National Party voters, due to the formation of coalition governments, are often coupled together. In this Climate Action Survey, and noting the sample are similar to 2019 Federal Election voting patterns, the distinction between the voters surveyed was noteworthy on a number of fronts.

Firstly, climate change was more important in the next Federal election to intending National Party voters (54%) than Liberal Party voters (45%). Not surprisingly, these National Party supporters were more likely to reside in regional areas than Liberal, Labor, and Greens supporters. That is, National Party voters were evenly split across metro and regional areas, Liberal, Labor, and Greens supporters were metro heavy (more than 70%).

There are a few possible explanations for the divergence in intending National and Liberal Party voters. Our survey found that Australian’s own observations are a principal source of information and trust on climate change, across all age groups but more so in older Australians. Proximity to drought, flood and changing weather is observed acutely by those living in regional and rural Australia, and so climate changes and impacts are lived and visible. Indeed, the difference between intending National Party and Liberal Party voters in reporting and acknowledging greater risk exposure to climate events and impacts is borne out in the survey results. Of course, some National Party voters could also be prioritising candidates unwilling to take action on climate although there was a consistent trend for National Party voters to answer in more pro-environmental ways than Liberal Party voters.

Overall, in this survey, the diversity in particular of regional National Party voters’ responses to climate change becomes apparent, marking their distinction from Liberal Party voters. These findings point to some of the cultural and political nuances of Australian voting and climate action, particularly in regional and rural communities. Further, our survey highlights younger voters, aged 35 and under, prioritising climate change at the federal election ballot box, being more concerned about climate change and more committed to climate action. This is significant given recent uptake of voter enrolment among younger Australians.

Demands for ‘Climate Action’ have become increasingly visible in Australian public debate. Environmental movement organisations and/or Environmental NGOs regularly call to abandon fossil fuels, ‘Stop Adani’, and phase out coal. These broad-brush strokes make for fitting media grabs and protest slogans but tell us little about what specific policies Australians are willing to support from governments, what Australians are prepared to do themselves and what their expectations are around who should pay for climate action.

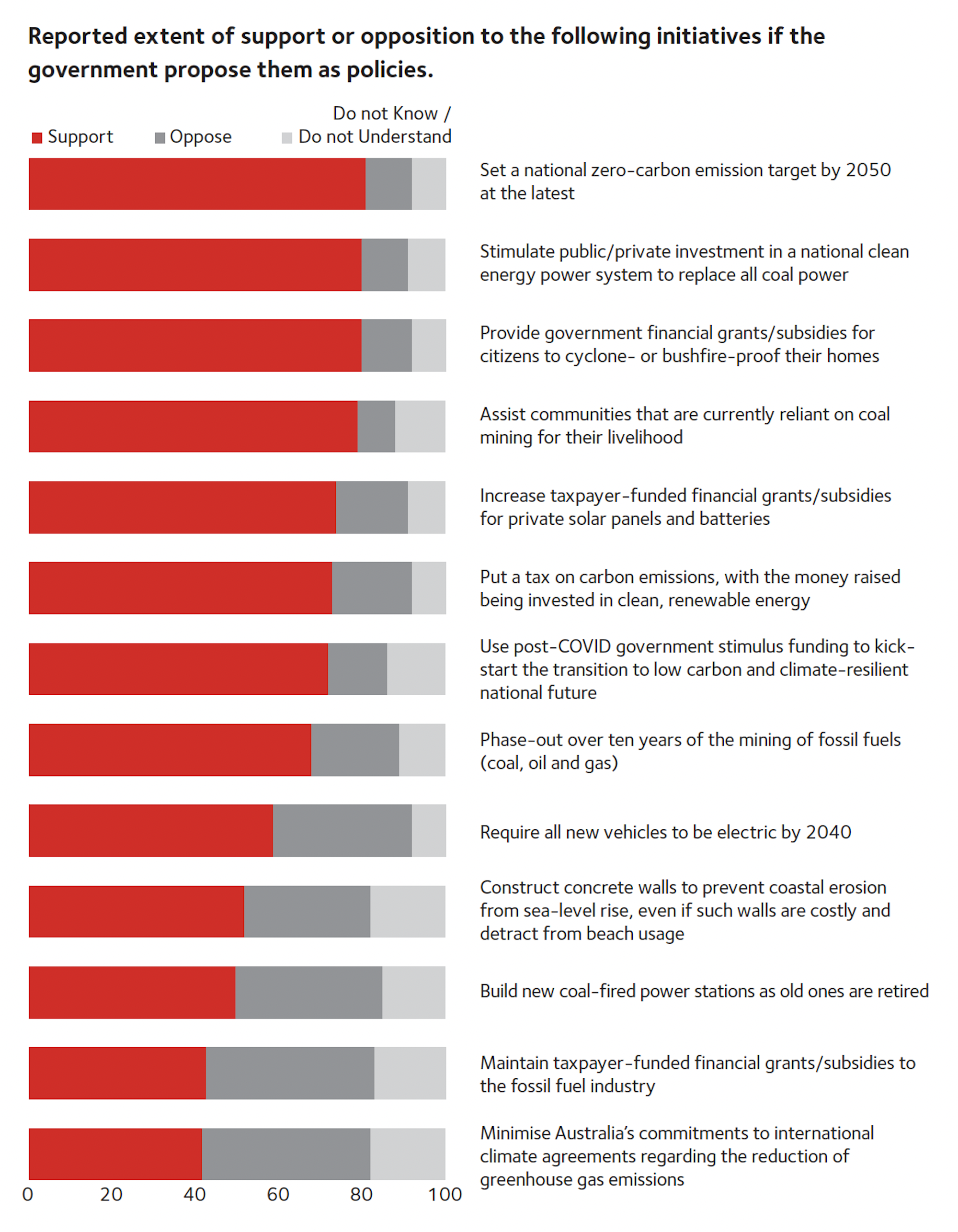

When considering government policies across a range of climate action options, the findings show that there is support from the majority of Australians for policies regarding future energy sources (e.g., restricting the construction of new coal-fired power stations), imposing a price on carbon, facilitating the uptake of electric vehicles, and assisting those whose livelihood is threatened by the shift away from fossil fuels.

While it is clear that Australians want governments to take climate action, the actions they are prepared to take in their private lives are more complex. Australians are interested in adopting environmentally friendly behaviours, and many are already doing so. For example, 55% expressed future interest in installing a home solar battery system, and 47% were interested in getting an electric or hybrid vehicle. Somewhat predictably, those who were more interested in taking these kinds of actions tended to be students or employed full-time, aged 35 years or under, university-educated, residing in a home where English is not the primary language spoken, or intending to vote for the Greens of Labor Party – the same characteristics of those most concerned about climate change and already reporting higher levels of pro-environmental behaviours.

Again, we do observe a willingness to adopt pro-environment behaviours change in other respondent segments, but at a lower level.

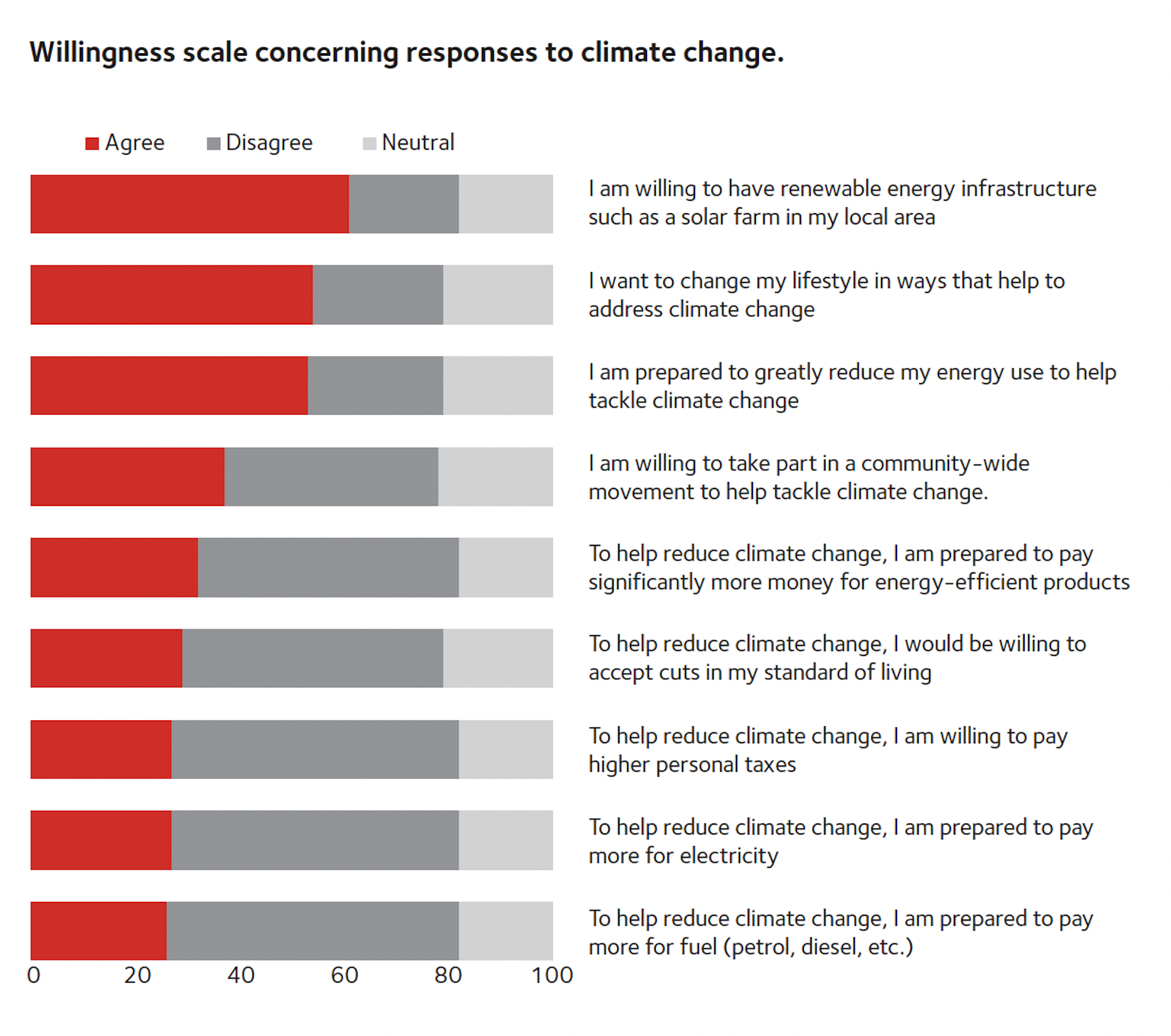

The majority of Australians report a willingness to change their lifestyle in ways that help to address climate change, evident especially in their response to energy use and renewables. However, they are generally not willing to pay higher personal taxes or increased costs for essentials like fuel and electricity from their own pockets to address climate change.

Interestingly, over half of the survey respondents indicated a willingness to move if their current residence was deemed uninsurable due to its exposure to the risk of flooding, bushfires, or other natural disasters.

Understanding what motivates Australians to participate in climate action is critical to developing effective communication strategies and for guiding planning decisions and policy responses. ‘Motivation’ of people and communities to take climate action is as equally complex and wicked a problem as climate change itself, especially given the diversity of circumstances and standpoints that characterise the Australian public. This complexity acknowledged, the survey revealed some clear possibilities to better communicate climate change in ways that are more likely to motivate and/or address barriers and challenges to action.

Easiest to identify are Australians who held strong values and opinions about their personal responsibility to take action against climate change. These tended to be younger students, inner-urban dwellers, university-educated, intending Greens or Labor voters, or residents in homes in which English was not the primary language spoken.

.

Around a third of Australians felt that their freedom to hold and express views on climate change was constrained. ‘Forceful’ communication tactics used by environmental groups and advocates received special mention. Australians responded more positively to empowering stories about partners/family/friends hope for our climate action. These stories may be more meaningful and less divisive than the ‘forceful tactics’ that some of our respondent’s perceived to be occurring.

Further, when asked about the likelihood that they would engage in six different types of climate change activism if a liked and respected friend asked them to do so, between 25% and 45% of respondents indicated they would or would definitely do so. Again, younger respondents, students, and intending Greens or Labor voters most often reported that they would engage in these types of activities.

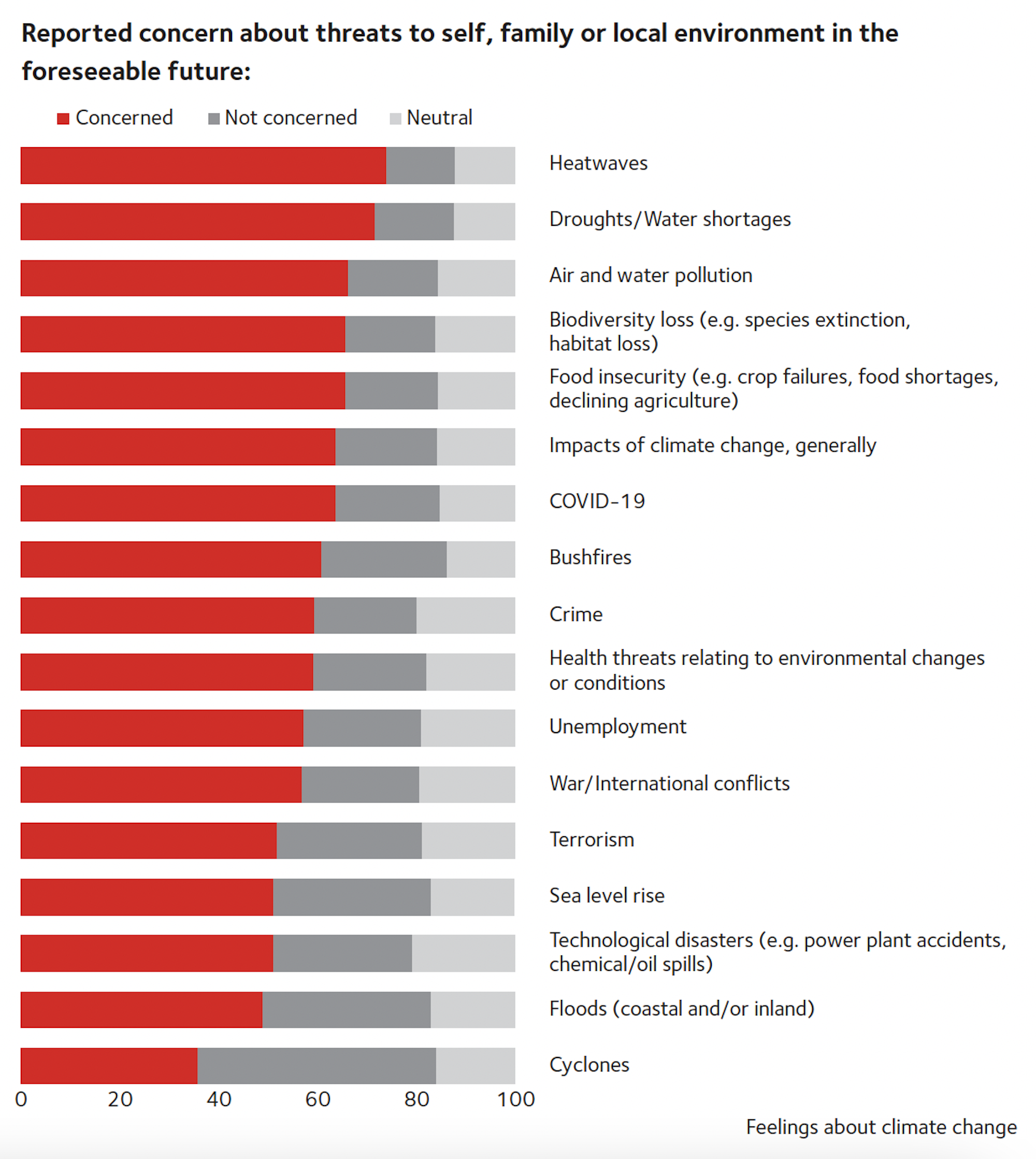

The recent flood crisis in Australia will deem the 2022 survey results particularly interesting. This survey, undertaken in late 2021, after the 2020 Black Summer bushfires, points clearly to the impact of disaster events on Australian responses to climate change, post a climate-related disaster event. Australians impacted by extreme weather events connected to climate change reported higher scores in their objective knowledge of climate change. Those who had experienced at least one natural disaster or extreme weather event (within the last year and over a year ago) expressed greater concern and distress about climate change. They were more likely to support government action to combat climate change, and they were more likely to engage in pro-environmental actions. Indeed, Australians who had experienced at least one natural disaster or extreme weather event, and those who had not experienced any such events, differed on nearly all the climate change variables.

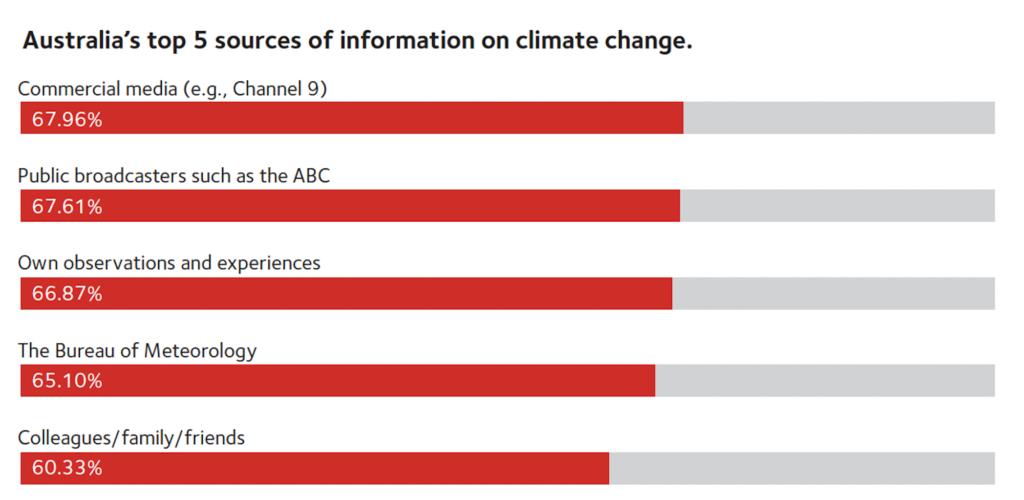

In the vast local and global media landscape, Australians have many choices about where to receive information on climate change. This can be both exciting and empowering and, conversely, overwhelming and confusing. Media literacy, particularly the capacity to identify reliable sources, is understandably and, at the very least, challenging at the current juncture.

Our survey highlights some important generational differences in the use of media to access climate change information. Interestingly, the five most trusted sources of climate change information were shared across all age groups. Concerningly, these five top sources of trust overwhelmingly represent scientific institutions and scientists and environmental organisations that often struggle for visibility in the mainstream news media – the very media from which most Australians access their climate change information. This speaks to the challenges scientists and scientific institutions confront in navigating the politics of climate change, where media processes and logics conflict with scientific reporting and communication of results.

The COVID-19 pandemic emerged during the creation and distribution of this survey. This presented an opportunity to ask our respondents about their level of concern for climate change or COVID-19. In response to one item, the same percentage (63.6%) of people reported being concerned about both. In response to other items, 72% expressed concern over climate change, whereas 80% expressed concern about COVID-19. A key point of this component of the survey is that people felt overwhelmed by the combination of global pandemic and the ongoing sustained climate crisis.

The Griffith Climate Action Summary Report for Policy and Decision Making (2021) and the Technical Report (2021) contain further results and detailed information on the conduct of the survey. The Technical Report is available on request from [email protected]

* A quota sample of resident Australian adults, stratified by gender, age group, and state of Australia, was recruited to conduct the survey. An online questionnaire was constructed through processes of consultation with stakeholders, review of the academic and opinion poll literature, and iterative pilot testing. The final version of the questionnaire comprised 188 single items/questions, approximately 30 multi-item composite scales, and nine open-ended questions. After removing cases that did not meet quality criteria, data from a final sample of 3,915 people (51.1% female, Mage = 46.6 years) were available for analysis. The survey broadly represents the Australian population based on markers of gender, age, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population and the distribution of Australian states and territories.

Dr Graham Bradley is an Associate Professor in the School of Applied Psychology, Griffith University. He is an applied social psychologist, with interests that cut across environmental, organisational, developmental, and health psychology. He has published more than 100 refereed journal articles and book chapters, and has been awarded research grant and consultancy funding in excess of AUD$2 million. For the past twleve years, his research endeavours have examined psychological aspects of climate change adaptation and mitigation, with a particular focus on the experiential, cognitive and affective correlates of pro-environmental behaviour. His expertise is in survey research methods and the analysis of large multivariate survey data sets. His work has been published in numerous journals including the Journal of Environmental Psychology, WIRES Climate Change, Ecological Economics, and Environment and Behavior.

Dr Graham Bradley is an Associate Professor in the School of Applied Psychology, Griffith University. He is an applied social psychologist, with interests that cut across environmental, organisational, developmental, and health psychology. He has published more than 100 refereed journal articles and book chapters, and has been awarded research grant and consultancy funding in excess of AUD$2 million. For the past twleve years, his research endeavours have examined psychological aspects of climate change adaptation and mitigation, with a particular focus on the experiential, cognitive and affective correlates of pro-environmental behaviour. His expertise is in survey research methods and the analysis of large multivariate survey data sets. His work has been published in numerous journals including the Journal of Environmental Psychology, WIRES Climate Change, Ecological Economics, and Environment and Behavior.

Dr Sameer Deshpande has over two decades working in the area of ‘marketing for a better world,’ Sameer has taught, widely published in academic journals, books, and conference proceedings, reviewed, and trained and consulted with government and non-profit organizations in India, Canada, Singapore, Australia, and the U.S. He is the Editor of Social Marketing Quarterly and Managing Director of Social Marketing @ Griffith.

Sameer has published studies testing the effectiveness of behaviour change initiatives using social marketing frameworks with particular emphasis on consumer-insights approach in a variety of contexts, including financial services to disadvantaged women, alcohol abstinence during pregnancy, safe sexual practices, promotion of alternative rides, responsible drinking, water rights, and physical activity. His book, co-authored with Nancy Lee, Social Marketing in India, has been well-received by the Indian academic and practitioner social marketing sector.

Associate Professor Kerrie Foxwell-Norton lectures in journalism, media and communication studies. Her research interests oscillate around relationships between communication, communities, culture and country. She has consciously sought projects which involve a direct engagement with communities. As a result, she has worked extensively with Australia’s community media sector, various coastal communities and works for and with, Indigenous community throughout Australia. Kerrie is a program leader in Griffith’s Climate Action Program and member of the Griffith Centre for Social and Cultural Research.

Natasha Hennessey Natasha has a Masters degree in Environmental Management, works as a Senior Research Assistant and Program Coordinator with the Griffith University Climate Action Beacon. Her research focuses on policy and program development for climate change adaptation, sustainability and conservation. She also has a strong research interest in climate justice, Youth engagement for climate action, as well as social and ecological resilience.

Natasha Hennessey Natasha has a Masters degree in Environmental Management, works as a Senior Research Assistant and Program Coordinator with the Griffith University Climate Action Beacon. Her research focuses on policy and program development for climate change adaptation, sustainability and conservation. She also has a strong research interest in climate justice, Youth engagement for climate action, as well as social and ecological resilience.

Dr Melissa Jackson is a transdisciplinary researcher and ‘pracademic’ specialising in sustainable, inclusive and just responses to climate change and sustainable development. Her recent research focuses on the theory and practice of transformative governance of water in Indigenous communities across remote Australia, focusing on the Torres Strait Islands. I also research questions relating to applications of systemic thinking, futures thinking collaborative learning and governance for sustainable development, community engagement, stakeholder engagement, facilitation and capacity building for climate resilient futures. I have extensive experience in research and project management, strategy and policy development in relation to climate change mitigation and clean energy, sustainable water, waste, food and climate adaptation.

Griffith University’s panel of politics experts have identified the seats to watch at the 2022 federal election.

Talk of ‘big dams’ to ensure water security, and ‘unlock regions’ to increase agriculture, has started again with the proposed $5.4 billion Hells Gate Dam on the upper Burdekin River in Queensland.

In 1973, the world’s post-war boom hit the rocks. Oil producers restricted supply, sending prices soaring. In the aftermath of this oil shock, nations like