Is The Voice to Parliament necessary?

Eddie Synot from Griffith Law School discusses why The Voice to Parliament is necessary and why this opportunity to change the Constitution should not be missed.

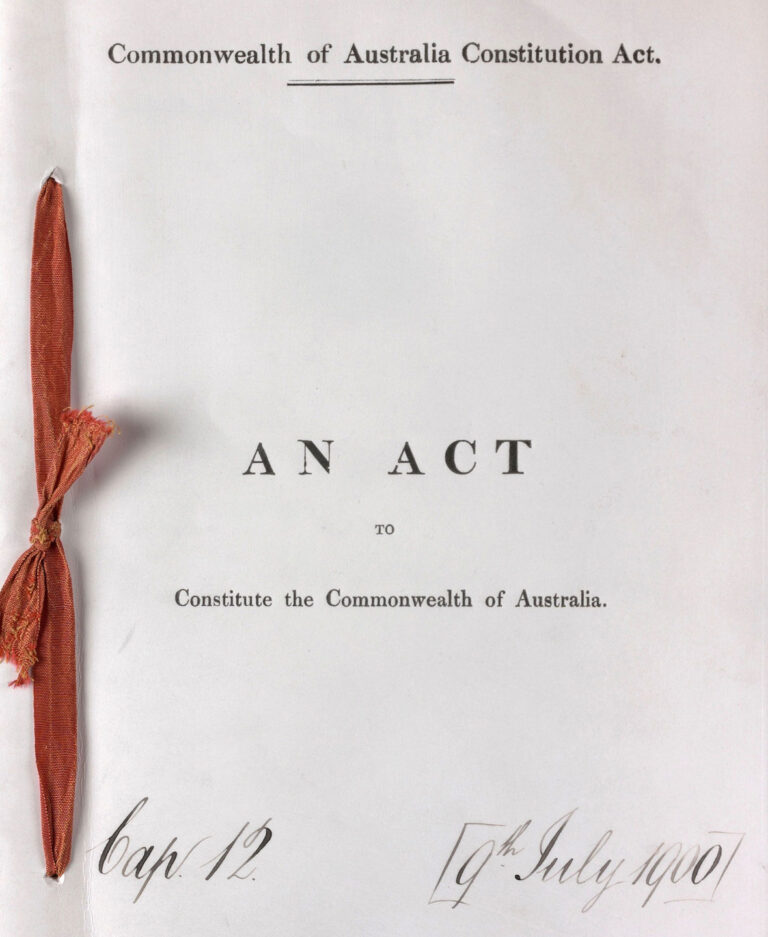

With the election of the Albanese government, the incoming Prime Minister committed to fully implementing the Uluru Statement from the Heart. Overarching the statement is ancient sovereignty and symbolic reunification from the Yolgnu word makarrata, understood to constitute the act of “coming together after a struggle”. The intent of the statement centers upon Australian constitutional recognition; at its heart is the re-centring of Indigenous sovereignty, and a subtext to achieve this. The implication within the statement somewhat challenges ongoing colonisation and occupation of our countries. With requests to explain the scope and role of an Indigenous voice for the Australian people, it appears at this early stage that the “voice” will serve in an “advisory” capacity only, without financial control or the authority to veto legislation. While the voice has been communicated as attaining majority community support, and emerges after extensive community consultation, Indigenous peoples in Australia are not a hegemony, and national consensus is yet to be achieved.

For over 230 years across the shifting fronts of armed resistance, protests, campaigns and diplomatic delegation, Land Rights and Treaty, have been rightly centred in the journey toward self-determination and Indigenous sovereignty. Proponents of the Uluru Statement’s centring, both white and black, may argue that Land Rights and Treaty are too radical a departure at this time for the liberal democracy at the heart of the new one-country Australia. From this vantage point, constitutional recognition and a voice may serve as a stepping stone, a real, concessional entitlement to a seat at the table of Australian administration. However, considering sovereignty and self-determination remain the primary aspiration for Indigenous communities, the shift towards the Uluru statement and a “soft reform of parliament” should be evaluated for deeper significance.

Positioned as the Uluru Statement from the Heart is—centred, within the sitting government’s Indigenous reform strategy—there is an apparent line of symmetry with critical race pioneer, the late Professor Derrick Bell’s theory of interest convergence. In the Australian context, on the surface, the rhetoric and optics of governmental benevolence have the appearance of good intent and justice; however, within dominant spaces of power, the advancement of Indigenous peoples has been recognised to usually coincide with parallel progression of non-Indigenous peoples. Importantly, as Goenpel scholar, Distinguished Professor Aileen Moreton-Robinson recognises, the threat of an organised Indigenous sovereign movement continuously presents as a danger to the logic of settler-colonial structures of government. In the absence of Land Rights, Treaty, reparations, and healing, all Australians should be cautious and thoroughly examine concessional offerings at this moment.

If the recentering of the Uluru Statement and its Voice to Parliament creates opportunity, what becomes the product, what is its strength, longevity, and purpose, and what role will education, schools, and teachers play? With school an integral tool in a racialised settler-colonial system of government, it is likely very little structural change will ensue. The fundamental restriction limiting meaningful progress toward makarrata is the school’s role in sustaining Australia as a settler-colonial state. In writing on Australian racism, Kamilaroi and Wonnarua scholar, Debbie Bargallie, outlines how the racial contract operates, leveraging systemic techniques of the law, policy, rhetoric, technology, and education, to wilfully exploit Indigenous peoples. Australia, by virtue of its enduring authority, inscribes the hierarchical boundaries of the racial contract through institutional discourse and space—such as the school system—and this orchestration is required for the maintenance of large-scale Indigenous oppression. Although Australian education is now concerned with the inclusion of Indigenous perspectives and Indigenous graduate capabilities for teachers, schooling, as a process of social engineering, remains tethered to historical practices intended to civilise, discipline, and assimilate Indigenous peoples. Australian schooling, therefore, is not without purpose.

As the movement toward an Indigenous voice to parliament builds from strategic Indigenous structural powerlessness, logical questions arise from the act of joining proposed by the Uluru Statement. In drawing upon Tanganekald, Meintangk Boandik scholar, Professor Irene Watson’s thoughts to critique the Uluru Statement and a voice to parliament, key questions must be asked to clear the road ahead. First, who are we now to join? Meaning, who are they and what are we now? What is it that is being joined, and what’s left and remains to join? What does it mean to join and who are they, the two joined now that they are joined? In what ways do they walk when joined and where can they walk—and are there any places left to roam? In visualising a makarrata, I see threads, spread among many threads and through this peace, the threads are woven to form yarn. But how we arrive at a place capable to weave remains unclear. Rigorous Indigenous representation in parliament should not be lost in the Voice as presently constructed. Consequently, further scope for discussion and strategic reflection garnered through education is necessary, to ensure the structures of Australian government are forced to fulfill the pressing needs of all Indigenous peoples.

*Troy wishes to acknowledge the input of Associate Professor Debbie Bargaille in writing this article.

Dr Troy Meston (Gamilleroi) is a Senior Research Fellow within the Griffith Centre for Social and Cultural Research and an Associate Investigator within the ARC Centre of Excellence for the Digital Child (QUT). His research seeks to enhance educational outcomes for disenfranchised learners and communities through the use of technology.

Dr Troy Meston (Gamilleroi) is a Senior Research Fellow within the Griffith Centre for Social and Cultural Research and an Associate Investigator within the ARC Centre of Excellence for the Digital Child (QUT). His research seeks to enhance educational outcomes for disenfranchised learners and communities through the use of technology.

Eddie Synot from Griffith Law School discusses why The Voice to Parliament is necessary and why this opportunity to change the Constitution should not be missed.

Professor AJ Brown discusses Australian constitutional law in relation to The Voice to Parliament as well as the process and outcomes of prior referendums on the nation’s culture and democracy.

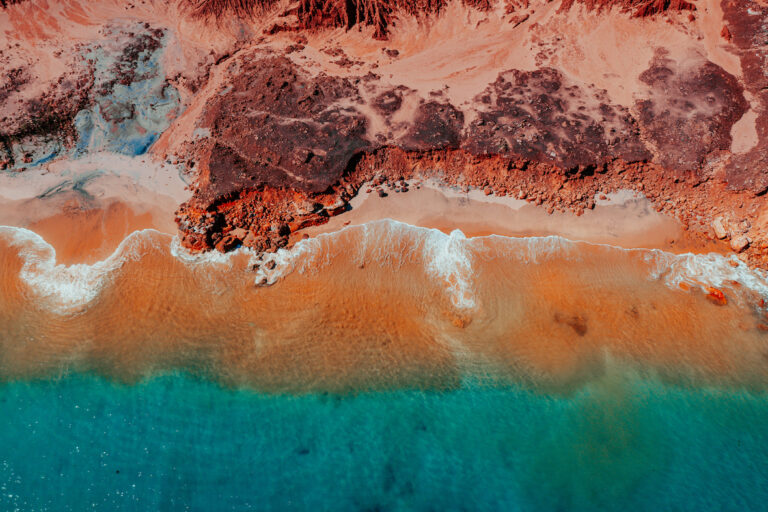

Professor Ciaran O’Fairchellaigh writes on the impact of criticisms of The Voice to Parliament will have on the development of Critical Minerals, the reserves of which are located on Indigenous lands. Critical Minerals are essential for renewable energy technologies, the demand for which is projected to rise significantly.