May 5, 2023

Cutting off one’s nose to spite one’s face is an expression used to describe a needlessly self-destructive reaction to a problem… a warning against acting out of anger, or revenge in such a way that it would only do more damage rather than help or heal a situation. This is how I feel honestly about our own Mob opposed to an Aboriginal Voice to Parliament.

The problem for many of our people is true reconciliation leaves no thrill of victory… they have become addicted to the fight and will never be satisfied with finding a resolution. You have to seriously question yourself when as an Aboriginal person you agree with the likes of Pauline Hanson, Andrew Bolt and Alan Jones, these people have never been our allies—extremism on both sides is motivated in ripping relationships apart and keeping our people separate from privileges that come with living in a developed world. A romantic ideology of justice that maintains trauma for many while privileged others find identity and a platform in their pain.

"You have to seriously question yourself when as an Aboriginal person you agree with the likes of Pauline Hanson, Andrew Bolt and Alan Jones, these people have never been our allies."

At Griffith University we run an ‘in conversation’ with Kerry O’Brien series. O’Brien, the former host of the 7.30 Report and Four Corners, winning six Walkley Awards for journalism during his career, interviews prominent Australians on contemporary issues of National significance. He recently interviewed acclaimed filmmaker Rachel Perkins who explained her motivation towards becoming a filmmaker was in being born to a people, who despite her famous father, had ‘no voice’ within ‘their own country’.

Perkins cited as motivation filmmaker Essie Coffey, ‘the Bush Queen of Brewarrina’, who left an indelible mark on Australian politics, arts, and culture. Another was Tracey Moffatt, a filmmaker and photographer, having held around 100 solo exhibitions of her work in Europe, the United States and Australia. There was also Lester Bostock, a Bundjalung man regarded as a pioneer of Indigenous media in Australia. Perkins explains how the silence broken by these pioneers awakened Australia to the brutality of its past in giving a voice to our people previously silenced and written out of history.

A voice that screamed injustice and spoke for the first time of the systematic massacres of Aboriginal people. Perkins speaking about how archeologists have since recorded a technique throughout Australia where Aboriginal bodies were dismembered into small pieces and burnt at great heat with bodies piled on top of each other in mass graves utilising fossil fuels to break down the bones and get rid of any evidence of the many massacres that took place.

Hearing this horrific personalised emotional account, Perkins was talking about her own family history of survival, makes you understand why so many non-Indigenous people are opposed to having an Aboriginal Voice. A Voice that derails the romantic tales of great white pioneers and free settlement. The Voice for Perkins became her time to “make a stand” and she became involved moving from observational filmmaker to a signatory to the Uluru Statement from the heart.

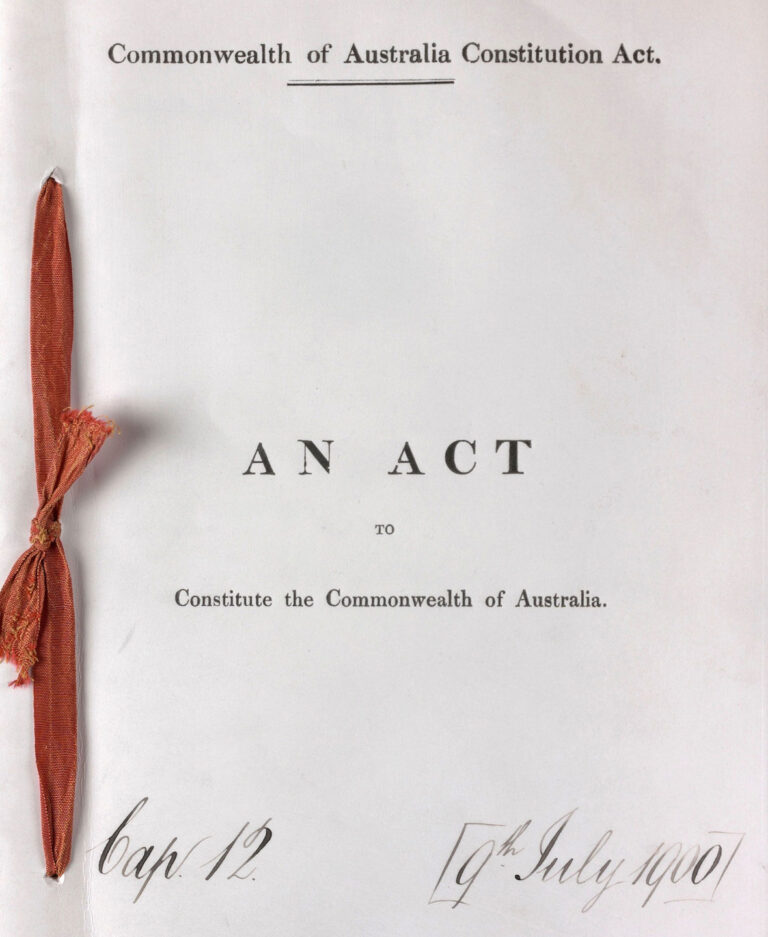

Rachel questions those within our own Mob opposed regarding the legitimacy of the process, stating that the Mob gathered in Uluru were a far greater number recorded for deliberations than for the Australian Constitution. She also cites the work done at a regional and then national level having thoroughly endorsed the process. Those who argue Treaty before Voice she answers calmly that the Voice remains a framework towards treaty…

Perkins describes the yes vote if successful will become a watershed moment, an event marking a unique and important historical change of course for this country… a turning point, an exact moment that changes the direction and most importantly, the way people think about themselves, their history and their country. She also says that finally our Black women from country will get representation to tell the country what they really feel about grog laws, funding for domestic violence, their culture and language.

Marcia Langton has been working with Tom Calma since 2017 to produce a report to the federal Coalition on a Voice to be legislated as an advisory body to parliament and government. For those who question the detail of the Voice together they produced a 272-page document that proposed local and regional voices feeding into a National Voice of 24 members.

The final report of the Indigenous Voice Co-design Process, commonly known as the Calma-Langton report, was submitted to the Coalition Federal Government in July 2021. It is now seen as the blueprint for the Voice, which under the Labor Government policy will be enshrined in the constitution if the nation votes yes.

Langton was present on March 23, when Prime Minister Anthony Albanese announced the referendum wording, in Parliament House. Her reflection when asked by a reporter on the day was one that comes from a lifetime of research and advocacy, defiance, anger, frustration and sadness:

“Each one of us here has been involved in a major initiative. The royal commission into Aboriginal deaths in custody. The inquiry into the forced removal of Aboriginal children from their families. The Don Dale royal commission … and in each case, we have doggedly recommended changes to stop the deaths, the incarceration, the early deaths, and the miserable lives and it is so infrequently that our recommendations are adopted”.

She then added, “… and each year, people like you come along to listen to that misery-fest, and each year, people go away wringing their hands. We are here to draw a line in the sand and say this has to change.”

Noel Pearson has lashed the Liberal party for what he called “a Judas betrayal” over its opposition to the Voice referendum. Criticism continues to mount over the opposition leader’s decision, announced recently, to actively campaign against the Indigenous Voice and force his frontbench to do the same. The reaction from former minister for Indigenous Australians, Ken Wyatt was to hand in his resignation in protest the decision. Mr Wyatt told the West Australian, “Aboriginal people are reaching out to be heard but the Liberals have rejected their invitation”.

Mr Wyatt, the first Aboriginal person to be elected to the federal House of Representatives, has long urged his Liberal colleagues to back the Voice before his resignation. He sits as a member of the Indigenous working group set up to advise the Albanese government on its referendum strategy and stood alongside the Prime Minister as he announced the wording for the proposed change to the constitution.

And finally, to those who argue that this is a form of apartheid classification based on race I say to you this is no argument about race this is about the correcting of the wrong side of our history and healing our future. This is not about race this is about geography, invasion and colonisation.

"... this is no argument about race this is about the correcting of the wrong side of our history and healing our future."

The Voice proposal recognises and acknowledges we were the first people here… and over tens of thousands of years we built the most sustainable eco-bio-diverse economy of any continent seen in the world.

The Voice recognises the tens and thousands of years behind these kinship practices and acknowledges our diversity and land management. It allows for the first time a western country to say invasion is wrong, genocide is wrong and just as with other dependencies built on our past such as fossil fuels and the move towards renewable energies this is a move towards sustainability and healing. This is a proposal allowing all Australians an inclusive future where we can all walk together and feel not only positive about who we are… but yes, even our past in healing our future.

This article was originally published in Koori Mail.

Author

Associate Professor Marcus Waters is the inaugural Dean Learning and Teaching (Indigenous) at Griffith University within the Office of the Deputy Vice Chancellor (Indigenous, Diversity and Inclusion), and a Convener of Open Learning, Sociology and Creative Writing.

Associate Professor Marcus Waters is the inaugural Dean Learning and Teaching (Indigenous) at Griffith University within the Office of the Deputy Vice Chancellor (Indigenous, Diversity and Inclusion), and a Convener of Open Learning, Sociology and Creative Writing.

You might also like

Is The Voice to Parliament necessary?

Eddie Synot from Griffith Law School discusses why The Voice to Parliament is necessary and why this opportunity to change the Constitution should not be missed.

The Voice to Parliament: Australia’s Constitution

Professor AJ Brown discusses Australian constitutional law in relation to The Voice to Parliament as well as the process and outcomes of prior referendums on the nation’s culture and democracy.

The practical effect of an Indigenous Voice: The case of ‘Critical Minerals’

Professor Ciaran O’Fairchellaigh writes on the impact of criticisms of The Voice to Parliament will have on the development of Critical Minerals, the reserves of which are located on Indigenous lands. Critical Minerals are essential for renewable energy technologies, the demand for which is projected to rise significantly.

Dr Kate Galloway

Dr Kate Galloway